Part 1: The Story of Mac

Part 1 from the book Murray MacDougall and the story of Triangle which was written by C. R. Saunders

Here was an idle corner of old Africa, devoured by anthills and long grass, tangled with tall trees and chance-grown shrubs, inhospitable to man, parched and withered through long months, yet with wild waters wasting in their season.

And one man came with his wagons, accompanied by a Swazi piccanin, and he loved this land and made it his home.

PART I

THE STORY OF MAC

Thomas Murray MacDougall was born on 4th March 1881, on the farm Auchnashelloch on Loch Awe, Argyllshire, Scotland, close to the family seat at Dunnollie Castle, about which Sir Walter Scott wrote "Nothing can be more wildly beautiful than the situation of Dunnolly, the ruins are situated on a bold and precipitous promontory, about a mile from the port of Oban." The MacDougalls were a proud and independent Highland family, known for their initiative and love of adventure, and so it is not surprising that many sons of the clan had seen distinguished military service down the centuries.

It was traditional amongst the Highlanders or those parts that on the birth of a son the head cowman should carve from a cow's horn a porridge spoon, and the infant MacDougall was duly presented with a fine spoon which is preserved in the museum to this day.

Murray MacDougall had a good start, with coarse-ground oatmeal porridge to begin each day, and plenty of fresh air and exercise on the farm, for his father believed firmly that youngsters should have a strict and vigorous upbringing. As a Highland lad growing up on his father's farm, Murray showed at an early age that he had inherited in full measure his ancestors' qualities of rugged resourcefulness and zest for life,

His father was a farmer who also owned interests in a banking concern in Glasgow, and during a severe recession of that time the family suffered crippling financial setbacks, and so it was that at the age of fourteen it was found necessary that the young lad should leave school and seek work in an attempt to assist the family. He found employment as a general hand in the shipbuilding yard of the giant firm Cammell, Laird & Co., where he soon gained the admiration and respect of his much older workmates.

It was here that MacDougall gained a love of things mechanical, as well as the practical expertise which was to stand him in such good stead in the years ahead, and as an interesting sidelight he gained something of a reputation for his ability to cook steak on a shovel for his workmates.

MacDougall was known as Murray to his family and his closest friends, and as "Mac" to everybody else, and he was never called "Tom" by anybody except in his late life. This appellation, to his great annoyance in his last years, was incorrectly credited to him by an ignorant or presumptuous Rhodesian press, presumably on the assumption that anybody with the first name Thomas should be called thus. (The management of Triangle Limited blundered similarly in the early 1960's by calling the company's first locomotive Tom MacDougall', and by so labelling a framed photograph hanging in the company's main office block. It is a fair bet that anybody reminiscing, either wistfully or proudly, about his close association with "Tom" MacDougall in the good old days, is guilty of name-dropping and did not really know him well.)

At the shipyards Mac met many interesting characters, and listened spellbound to their stories of distant places, and his urge to travel and thirst for adventure led him to sign on as a hand on a cattle-boat which was sailing for the Argentine. He left with the blessing of his family, and throughout his life maintained the strong family ties of his clan, despite his fiercely independent spirit and prolonged absence from the Highlands of home. He treasured through all his wanderings his tangible links with his clan and family, among which were a locket given him by his mother and father, containing their miniature portraits, and an inscribed bible from his mother, and all his life he had a MacDougall tartan rug on the end of his bed.

Having arrived in South America, he made his way through several countries, seeing something of Brazil, serving in President Castro's army in Venezuela in 1898, and eventually landing up in British Guiana (now Guyana), where he obtained employment in the sugar-cane fields of Demerara, for a salary of six pounds a year and his keep! A mistaken idea has somehow arisen that MacDougall obtained his inspiration to grow sugar-cane at Triangle in later years' because he recognised instantly the similarity between conditions there and those of Demerara. Nothing could be further from the truth, as the Guiana fields were in swamps, requiring ingenious drainage systems to avoid flooding, and providing an interesting opportunity to transport cane to the mill on rafts.

Mac acquired a life-long aversion to pork while at Demerara, as there was apparently a large population of feral pigs gone wild and living in the cane. These were called to be fed on molasses by blowing on a cowhorn and they were regularly harvested and used as a staple ration for the men. One skill of great subsequent benefit which Mac picked up at Demerara was that he learned the principles of surveying, a factor essential in Demeraras canal and drainage system, and later to be a priceless advantage in his early days at Triangle when laying out his irrigation system.

The hard work and rigorous outdoor conditions in South America ensured that MacDougall matured physically, and by his twenty-first birthday he had filled out and was a tall and strong man.

AFRICA CALLS

Early in 1902 Mac again succumbed to the urge to move on, and he eventually obtained a working passage in a ship bound for South Africa from the United States, whence he had travelled after leaving Guiana.

On arrival in Cape Town Mac enlisted in the South African Constabulary to serve the Crown in the Boer War, but before he saw active service the war ended, and Mac was discharged from the force and set about finding a job. He travelled to Natal and joined a cartage firm. He soon demonstrated a natural flair for handling transport animals, and in a very short while he obtained a wagon and a team of mules of his own, and became an independent transport rider. His services were much in demand, and he carted supplies through Northern Natal and Swaziland, eventually making his way to the Eastern Transvaal, where there was great activity on the goldfields in the Barberton/Lydenburg/Pilgrim's Rest area.

The bracing climate, bare hillsides, and rushing mountain streams must have reminded Mac of his Highland home, and this impression was probably reinforced by the presence of many of his countrymen in the district. Indeed there had for so long been so many Scots working in the area that President Burgers of the Transvaal Republic, on a visit to the region in 1872 named one particular camp MacMac, a name which has persisted to this day. MacDougall spent three happy and vigorous years in this historic district, further enhancing his reputation as a skilled transport rider and a man of good character and high principles.

During the summer rains it was not possible to do much work in the haulage business, and Mac took to travelling around and seeing the country at these slack times. So it was that in 1906 he travelled north on horseback, leading a pack animal with his kit. He crossed the Limpopo and pushed on northwards through the lowveld bush until he reached the Mtilikwe River, in which vicinity he spent an enjoyable few weeks hunting, and making the acquaintance of the handful of Shangaans who lived along the lowveld rivers of this wild, unexplored, and virtually uninhabited corner of Southern Rhodesia.

MacDougall fell in love with the area, probably among the first white men to fall victim to the strange fascination of the lowveld, and he vowed to return one day.

Trekking back to the Transvaal, he secured a contract at Pilgrim's Rest carting supplies for the hydro-electric scheme being constructed on the Blyde River, below the Bourke's Luck pot-holes, to supply power for the goldfields. For two years he worked on the scheme, saving his money and investing in better wagons and pack animals, taking time off to serve as a volunteer in (he Zulu Rebellion over the border in Natal in 1907. and being awarded the campaign medal.

At the end of 1908 he decided to make the move to Mashonaland, and he led a party northwards through the wild country he had traversed two years previously. In his party were six white men, a coloured man, and nine blacks, including a young Swazi piccanin, Tom

Dunuza, who had joined Mac at Carolina in the Transvaal on a previous trip, and who was later destined to become one of the great characters of Triangle.

Crossing the Limpopo, the party trekked straight on to Salisbury, where Mac lived for the next four years, delivering stores and supplies, mining equipment and building materials to the gold mines in the Mazoe Valley and surrounding districts. He became famous throughout Mashonaland for his skill with his mule teams, and once drove a fully laden wagon up the very steep hill to the Bernheim Mine at Mazoe, which was regarded as an extraordinary feat in those days.

In 1912 famine following prolonged drought threatened the south-eastern area of the country, and the Government appealed for help in carting grain to the starving African people of the Victoria district. Mac travelled with his grain down to the Bikita and Zaka area, and took the opportunity to revisit on horseback the uninhabited area on the lower Mtilikwe. He experienced again the irresistible fascination with which the lowveld had earlier gripped him, and decided to do something about it.

On return to Salisbury he applied to the administration for rights to 300000 acres of land between the Mtilikwe, Chiredzi and Lundi Rivers, but, as there were no maps of the region and no surveys had been performed, there was an understandable delay in formalising his grant, but he was given an option on the land. Mac moved to Triangle, followed naturally by the sturdy young Tom Dunuza, but before he could contemplate any development, the Great War broke out in 1914.

MAC THE WARRIOR

Along with so many of the cream of the Empire's youth, MacDougall answered the call to arms, travelling from Triangle to London, and enlisting in the First King Edward's Horse. He went abroad with the British Expeditionary Force, and served with distinction in the First Battalion, the 18th London Regiment, attaining the rank of Captain. His great experience with the mules so vital to the war efTort in the First World War led to his appointment as Brigade Transport Officer. He was twice mentioned in dispatches, and was awarded the Military Cross. His army pay-book, preserved in the museum, records the award as follows:

"CITATION ON OCCASION OF AWARD OF MILITARY CROSS TO

LT. T. M. MACDOUGALL.

Lt. Thomas Murray MacDougall, London Regiment, for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty when bringing up a train of pack mules with supplies to his battalion. With exceptional skill and fine judgement he sent his convoy singly through heavy barrage, afterwards re-assembling them and delivering his supplies without casualties. This occurred in complete darkness, and his example of personal courage and decision was invaluable to his men.

Battle of Messines

June 7th 1917."

MacDougall took great pride in his work, and his iniative and practical bent of mind led to his invention of an ingenious mule saddle designed specially for carrying ammunition for the field guns.

On his discharge from the army after the armistice, Mac's Commanding Officer sent him the following commendation:

"Lt. T. Murray MacDougall acted as brigade transport officer for almost a year — his thorough knowledge of animals and transport work was of great value at all times. He understood the management of men and how to get things done. He has always behaved with gallantry, notably in the Ypres Salient — the operation including the battle of Cambrai in November and December 1917, and during the withdrawal after the great German attack on March 21st 1918, when he succeeded in bringing all the animals and transport of the Brigade intact through an extraordinarily difficult and trying period — an extremely capable and efficient officer.

William J. Mildren

Brigadier General

Commanding

141st Infantry Brigade"

As soon as MacDougall was brought back to London with his unit at the end of the war, he hurried back to Salisbury intending to lose no time in returning to his beloved lowveld to start development of his ranch, but he was furious on finding that while he had been on active service his land had been promised to somebody else. Unable to make any headway in his protestations in Salisbury, he returned to London determined to assert his rights in the highest places. In later years he recalled with a broad grin how he demanded, and was granted, an audience with the Directors of the British South Africa Company, during which he thumped the boardroom table and expounded his claims in uncompromising language.

To their eternal credit these influential gentlemen upheld his appeal, and, clutching a precious document authorising his grant to his promised land, Mac boarded a steamship bound for Cape Town.

When MacDougall commenced his return to Cape Town the great 1919 influenza epidemic was raging, and many of the crew were smitten by the disease during the voyage. MacDougall's strong constitution enabled him to escape the illness, and he fell to willingly to lend a hand wherever needed. Thus it was that his tremendous initiative and versatility were fully utilised by the captain of the ship, and Mac found himself acting at various times as purser, steward, assistant mechanical engineer, and navigation assistant.

On arrival in Cape Town it was round that the flu had the city firmly in its grip, and many poor people, in particular, were dying from the disease. An appalling situation had arisen due to a high mortality in District Six, as most people were afraid to enter the slums lest they too should succumb. Shrugging off the danger, MacDougall undertook to transport bodies of deceased persons from District Six to the cemeteries, the only payment he requested being a case of Scotch whisky.

He eventually arrived back in Salisbury, re-established his rights to his land, and was granted an option on 300 000 acres of land, now roughly comprising the properties of Triangle, Buffalo Range and Hippo Valley Estates, for an ultimate purchase price of fourpence an acre.

EARLY DAYS ON TRIANGLE

Murray MacDougall had always wanted to ranch cattle, and in Fort Victoria he met another well-known character, Mark Spraggen, with whom he struck up a partnership. They named the property Triangle after the registered cattle brand which Mac purchased from a fellow farmer named Van Niekerk, as the poor chap was going out of business and had a very simple brand which almost defied alteration in a period when rustling and brand-changing was not uncommon. For a few pounds Mac purchased both the registered brand itself, in the shape of a simple triangle, and the branding irons to go with it.

Mac rode down to the ranch with his cattle and his wagons, forded the Mtilikwe, and pitched camp under a large baobab tree across the Cheche stream, not far from the present new supermarket. It was said by his old hunting partner Scrubbs Hartshorn that Mac spent his first night on Triangle Ranch under the old marula tree on Mac's Hill beneath which his ashes now lie in a simple stone monument.

A clean water supply was one of the first necessities, and with a handful of Shangaans armed with picks and shovels, and a few sticks of dynamite, he sunk a well near the Cheche, close to the present mill site, making a rough windlass from mopani poles, by means of which the earth and stones, and eventually the water, were hauled to the surface in a bucket on a rawhide rope. Then came the construction of the cattle dip, on the eastern bank of the Mtilikwe River close to the present C.A. Gibbs Bridge.

MacDougall then set about making a home for himself, and for the site chose Mac's Hill, making his first dwelling of sunbaked "Kimberley" bricks, and topping it with a high roof thatched with reeds. The site commanded a splendid view of the country for miles around, and a breeze usually made the site more tolerable than the baking plains below. One morning Mac was busy in the workshop, when, hearing a footstep behind him, he turned to see a strapping young man standing there, proud and erect. "Master, 1 have come", he said. It was Tom Dunuza, who had wandered away from Triangle seeking work elsewhere when Mac left for the war. Hearing on the grapevine of Mac's return to the lowveld, he had travelled day and night to rejoin him, never doubting the rightful glad welcome awaiting him. He soon threw himself into the many tasks Mac allocated to his supervision.

MAC'S CATTLE

Mac's cattle thrived on the sweet grazing, for the lowveld is splendid ranching country, and MacDougall was extremely proud of his burgeoning herd. There were many lions on the ranch, and they accounted for a number of the cattle, and leopard and wild dog also

exacted a toll, particularly of the younger stock. For a brief period Mac also suffered losses from rustling by tribesmen from across the Lundi River, but this ceased dramatically after one particular incident: a herd-boy reported that he had found a dead calf, and on going to investigate, Mac saw crouched over the carcass a form which he took to be a wild dog. He fired, killing the culprit instantly, and was amazed to see an African man sprinting away from the dead calf into the bush. On closer inspection Mac found that he had in fact shot and killed a cattle thief in the act of butchering a young calf. His companion escaped to spread the word, and no further trouble was forthcoming from that quarter. Mac proceeded to report the matter to the police, but after a brief investigation no further action was taken.

There was an abundance of wild game on the ranch, and hunting both for sport and for rations was a regular pastime, impala, kudu, zebra, buffalo and sable were plentiful, while many Lichtenstein's hartebeest were present, and roan antelope were not uncommon, both these latter animals being used for rations. Eland were common at certain times of the year, and elephant were found all over the ranch, particularly in the rainy season. Hippo were numerous in the Mtilikwe and Lundi Rivers and were used for rations and for the making of rawhide riems and sjamboks when cut into strips, hung from a tree, and twisted with a heavy stone as a weight. MacDougall stated that he never saw giraffe or wildebeest anywhere north of the Lundi River, and certainly not on Triangle ranch. Guinea fowl and francolin were plentiful, and the fishing for bream in the rivers was good. Mac was a keen birdshot and angler, and many hunting and fishing parties were arranged with visitors and a few neighbours such as the Francis Brothers of Bangala Ranch. In later years it became traditional for successive Governors of the country to make an annual winter hunting and fishing trip to the Chipinda Pools on the Lundi River, and the well-read outdoorsman from Triangle Ranch was always a welcome guest at His Excellency's camp. One visitor who came to Triangle every year for many years to spend the winter with Mac was his sister Marjorie, in later years tragicallv killed in the London 'blitz' in the Second World War.

Unfortunately, the success of the ranching venture was short-lived as cattle prices fell to rock bottom levels with the post-war depression, and by 1922 Mac had to sell most of his cattle, retaining only a small dairy herd and his trek oxen, and the partnership with Mark Spraggen was dissolved. Spraggen moved to Fort Victoria, and from Marumbini on the Sabi-Lundi junction, where the partnership had established a small trading post, he opened a recruiting organisation supplying labour to the gold mines of the Witwatersrand.

Spraggen acquired a dubious reputation which was not really deserved, and he was not the only suspect character with whom Mac associated. At one time he befriended Cecil Barnard, known as

"Bvekenya", a renowned ivory poacher, and on the only occasion Barnard was apprehended by the B.S.A.P., for shooting a hippopotamus, MacDougall saved him from going to gaol by lending him £10.0.0 to pay a fine. It was said that MacDougall always knew from the "bush telegraph" when a B.S.A.P. trooper left Zaka on horse patrol to the Triangle area, but on one occasion his intelligence system failed him, and a young trooper came riding up the hill just as Mac was entertaining Bvekenya, at that time a wanted man. He was hastily bundled under Mac's bed, where he remained safely hidden until the policeman had finished his tea and spent an hour or two chatting to his host.

Lest the impression be gained that MacDougall was in some way disrespectful of the law, let me hasten to add that he was nothing of the sort, but as a man's man in a rugged frontier area he had befriended many an interesting character of the times, and a rough camaraderie invariably grew up between such independent souls in remote areas.

THE EPIC IRRIGATION STORY

Murray MacDougall's cattle bubble had well and truly burst, and he turned his attention instead to the irrigable potential of the rich alluvial soils of the northern section of the ranch, determined to bring water from the Mtilikwe River to his lands. He appealed to the Government for help, and in 1923 an engineer travelled from Fort Victoria by mule cart to survey the scheme. A furrow was pegged out, and a site on the river bank selected for the construction of a weir. But when Mac came to dig for the foundations he found nothing but sand, and in any event if the weir site were moved upstream, a considerably increased acreage of irrigable soil would be brought "under command" of his irrigation furrow. So it was that he moved a little way upstream and started to build the Jatala Weir on a ridge of rocks which ran right across the wide river, and which he had always considered to be the most favourable site for the venture.

The fact that the Government's Irrigation Department considered him to be impudent, misguided and high-handed, and the presence of two large granite kopjes directly in the path of his proposed canal from the amended weir site, did not in any way deter this rugged and resourceful Scot.

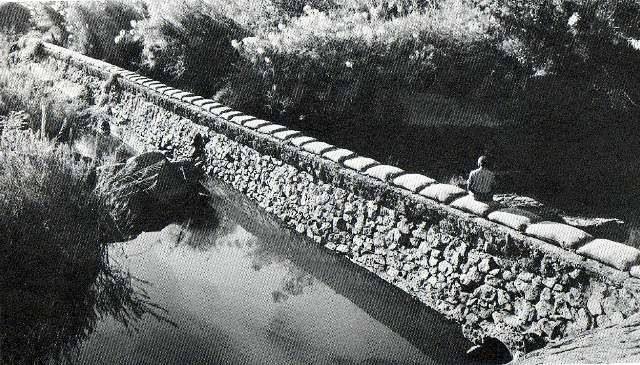

Triangle's pioneering irrigation engineering works are now a National Monument, and a bronze plaque on site records the facts simply as follows:

"From this weir, built in 1923, Thomas Murray MacDougall led water from the Mtilikwe River through two tunnels, hewn by hand over seven years for a distance of 1400 feet through solid rock, and thence to his lands through a canal eight miles long. This historic enterprise was the first development in the Lowveld's great irrigation project.

Erected by The Historical Monuments

Commission of Southern Rhodesia

It is an inspiring experience to visit this site today, and to sit quietly on the rocks and contemplate this place in the years of its construction.

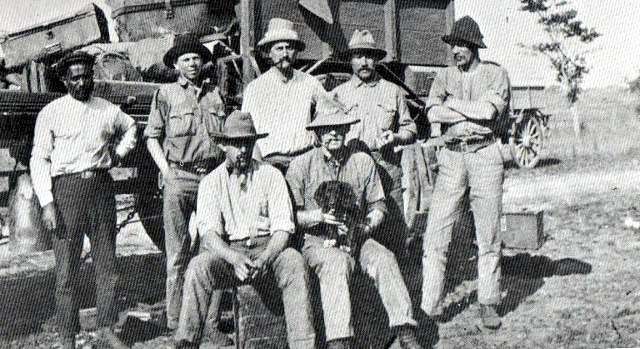

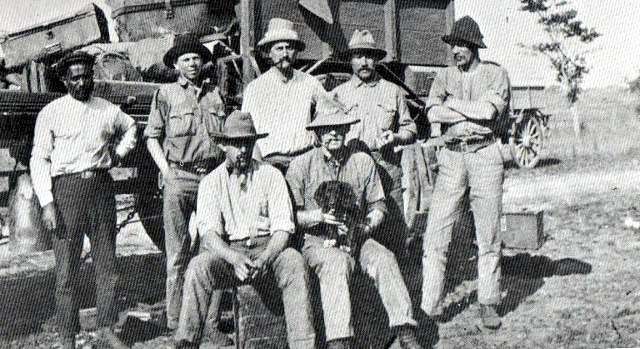

The party that trekked to Rhodesia in 1908. MacDougall holding the puppy.

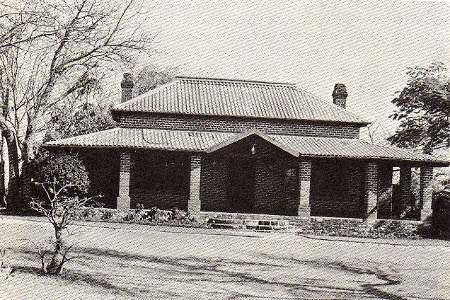

THE OLD AND THE NEW

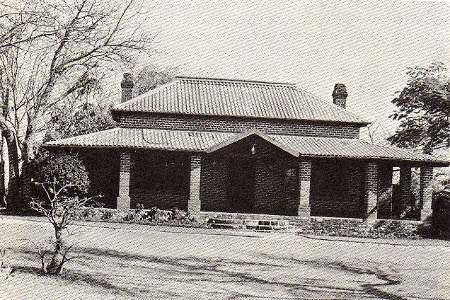

MacDougall's first home on the hill (Above), and his new homestead as it is today on

exactly the same site (Below.)A

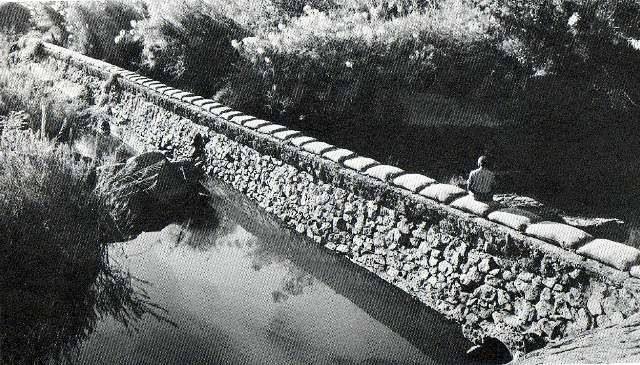

MACDOUGALL'S JATALA WEIR

The first irrigation engineering development in the Lowveld and now a National Monument.

MacDougall with his first mature cane.

Not only the tunnels were remarkable as an early civil engineering feat in an age and at a location without sophisticated mechanical equipment: the enormous ditch between the two tunnels, dug by two oxen pulling a dam scoop; the massive approach to the Musiswidzi siphon; the great siphon itself, characterised by massive homemade concrete pipes built on site and still bearing the imprint of the shuttering — all these works performed in arduous and remote conditions by a single-minded untrained Scot and his willing toiling team of Shangaans, sweating and labouring with picks and shovels, shifting earth and rocks with wheelbarrows and spans of oxen; all this identifies Thomas Murray MacDougall as a man apart, a true pioneer who was a visionary, and spared not himself to realise his vision. He saw this parched and wild land and its rich and ancient soil, and he knew that if only it could have the blessing of plentiful and regular water, it could produce an abundance of food crops for man.

MacDougall shouldered aside the protests and obstructions of a sceptical Irrigation Department (he named them the "irritation department"), but one civil engineer, a fellow Scotsman named Cecil Robertson who had designed the Muswiswidzi siphon and who was to have a profound influence on Triangle over many years, saw that Mac was not deluded, but gifted, and "Robbie" stood steadfastly by the lowvelder all his days, supporting and assisting him by any means possible, and taking MacDougall's side against his critics.

During the long years before Mac's irrigation scheme was completed, and following the misfortunes of the cattle venture, he took a number of jobs, particularly transport riding, to meet his expenses and provide a simple living.

At last in 1931 the water was led for the first time on to the prepared and waiting lands, and Mac wasted no time in planting a variety of crops, watching with enormous satisfaction and pride as the seed germinated and the plants flourished.

THE BUILDING OF THE HOMESTEAD

During those long months when the floods prevented work on his tunnels, Mac diverted the attention of his work force to the construction of his homestead and headquarters on Mac's Hill, replacing his first temporary home with more substantial buildings in place of his original rondavel and rough open circular dining room. He built a living room on the present house site, and a combined bedroom-office which still stands today and in which "The Story of Mac" is portrayed, but he soon

become irritated with his living room, and decided to rebuild it in more dignified and substantial form.

He made his own burnt bricks, found a limestone deposit near the Lundi River and burnt his own lime for the pointing between the bricks, and set about improvising a most effective pit-saw by means of which he sawed his own timbers from the estate. Thus was built in 1926 the magnificent pioneer home which today is a National Monument.

Most of the woodwork and superb ceiling panelling was made of Pod Mahogany (Afzelia quanzensis), Lead wood (Combretum imberbe) and Knobthorn (Acacia nigrescens) which was selected, felled, logged, sawed and fashioned by Mac and a remarkable home-taught African craftsman named Willem, who had come from South Africa with Mac. Mac made his own door and window fastenings from pod mahogany, and, as in his Highland home, a fireplace and high ceilings were included as a matter of course.

MACS OUTBUILDINGS

Several solidly constructed rondavels were erected for use by visitors, and a separate kitchen added at the rear. As a bath was both temporarily unobtainable and expensive, Mac fashioned his own of cement in a small bathroom on the north side of his residence, and only in later years was a conventional bath installed next door. A "Rhodesian boiler", 44 gallon drum heated by a wood fire, provided a plentiful supply of hot water, but Mac's early guests complaincd that while the water might be scalding, the cement bath had a decidedly chilling effect on the rear end of the bather! On one memorable day Mac had staying with him a guest, who was occupying the rondavcl nearest the main dwelling, and they had gone out fishing early in the morning. When they returned at dusk, the guest was startled by a leopard which dashed out of his rondavel as he prepared to enter. No-one was harmed, but what a story he had to take back to Salisbury with him.

But undoubtedly the most famous and picturesque outbuildings were the MacDougall toilets, known as "longdrops" of which there were two. Access to the one still preserved as an integral part of the National Monument involved a steep descent of rough-hewn stone steps skirting a precipitous drop. There was no door, and the open doorway faced east, with an outlook over an open plain below the hill, later developed into an airstrip, and now the site of Rufaro Village. Early visitors spoke of the magnificant game-viewing from this convenience as one sat and contemplated life, warmed by the rising sun. The other loo', further west, faced the setting sun, and has now collapsed.

Mac's toilets, situated as they were over deep clefts in the rocks, required no plumbing, but a water reticulation system he devised on the hill had a disastrous fate. All water for the homestead had to be hauled up the hill in an improvised bowser drawn by two patient and powerful oxen, and Mac decided to utilise the rainwater off the roof of his main dwelling. A guttering system was installed and led into a succession of home-made covcrcd round concrete tanks, from the bottom one of which water was to be pumped into a huge concrete reservoir built behind his bedroom.

Other structures on the hill were concrete tanks for curing riems from gameskins, using mopani bark to tan them, and a small slaughter pole where carcases of game animals shot for meat were hung.

Stores and supplies had to be fetched from Fort Victoria by oxwagon, travelling along the old road through Chivamba's and the Bikita and Zaka districts, and this route was impassable to the wagons during the rains, when horseback was the only means of transport. In later years when he had cut a new road MacDougall occasionally collected supplies from Messina for variation, his wagon being absent for several weeks on such trips.

Mac was particularly proud of his wheat, a sample of which was sent to London by the Ministry of Agriculture, receiving a most enthusiastic and favourable report from a prospective importer. He also grew magnificent lima beans and achieved success with an early cotton crop, while sub-tropical fruit such as bananas, mangoes and pawpaws nourished in the local conditions, and Triangle citrus, particularly MacDougall's grapefruit, developed a considerable

reputation. Mac was inordinately proud of his "baccy", the burley tobacco he grew on the alluvial soils on the north bank of the Lundi, east of the great hill Bendezi, where a trusted Shangaan friend named Marilele had his home. Twists of Mac's tobacco were sold in trading stores all over Victoria district, many owned by personal friends and frontiersmen like the colourful Australian Ben Brewer.

Mac's crops flourished, he cleared more and more land for irrigation, and soon had more than two hundred acres developed. Many intrepid visitors came to admire his efforts, and MacDougall entertained them royally. His sister Marjorie came out from Scotland each winter to stay for several months, and the remarkable Brig. E. P. Hartshorn, a tough one-armed military veteran of great charm and artistic talent who was Mac's hunting companion for many years,

made a long pilgrimage from his home in Johannesburg, and later in Swaziland, each winter to hunt on Triangle and the surrounding lowveld. Hartshorn was employed in the public relations field for the giant Schlesinger organisation in South Africa.

DISASTER — AND THE COMING OF SUGAR CANE TO THE LOWVELD

So well did Mac's winter wheat do, that he made arrangements to import a combine harvester from Massey-Harris in Britain. However, just as the cars were beginning to ripen, a vast horde of quelea, (a small gregarious species of seed-eating finch), descended and stripped the crops. Mac sent a terse telegram to the Massey-Harris agent in Salisbury: "Cancel harvester. The birds have done it for you." Worse was to follow, and a succession of swarms of locusts passed over Triangle, destroying all Mac's crops, in spite of the traditional banging of tins and various methods of destruction by which Mac and his helpers attempted to stem the invading hordes.

Gloom descended over the homestead, but Mac refused to give in. Brigadier Hartshorn recalled in later years how he had been staying at the ranch, and Mac had been unusually restless and irritable. Long after Hartshorn had retired for the night, he awoke to see a lamp burning in Mac's bedroom, the shadows revealing that Mac was pacing round and round his room, from which mumbled muttering could be heard. He called out "What is it Murray?", and MacDougall came down to his rondavel, sat on his bed, and said "I'll fix the little blighters, Scrubbs! I'll grow sugarcane like we used to in Demcrara." Thus, in an inspired effort to beat the pestilential red-billed quelea and red locusts which threatened the first agricultural development of the lowveld, the determination of this rugged Scotsman brought about a decision which was to change the face of the area. So it was that in 1934 he applied for permission to import a load of seed-cane from Natal.

His application was treated with disbelieve in some circles, but with the help of C. L. Robertson, who had then become Director of Irrigation and had always supported his countryman, MacDougall was eventually granted a permit for three lengths of cane. Armed with the permit, MacDougall set off for South Africa in his recently acquired Model A Ford, declaring his meagre three sticks of cane on his return to Beit Bridge, but neglecting to mention the much larger number he had lashed under his motor car He later drove across a drift on the Limpopo, bypassing the Customs, with a further lorryload of Natal cane. From these humble beginnings was to grow a massive industry.

MACS MILL

MacDougall's cane grew with splendid vigour in its new lowveld home, and it is probable that he obtained from the cane's donors in Natal a sprinkling of sound cultural advice to add to his previous experience gained many years before on a different continent. For several patient years now he set about bulking up a cane crop from his small initial planting, always looking steadfastly ahead to the longed-for day when he would make his first sugar.

He had already set about planning the acquisition of the milling and factory machinery necessary to wrest the sweet reward from the ripe cane stalks, and feverish activity and much coming and going from the ranch house on the hill was inevitable. Mac went again to Natal to secure his requirements, and with the great and knowledgeable assistance of a Mr. John Murray of Durban, he soon had contracted to purchase a variety of second-hand equipment from various Natal organisations, principally at Beniva, La Mercy, Umfolosi and Mount Edgecombe. The total cost of the milling equipment was £4 500, and in part payment for their Beniva milling equipment, the firm of Crookes Brothers accepted an offer of shares in the Triangle venture.

The first necessity was to cut a road from Triangle to the main Beit Bridge/Fort Victoria road at Ngundu, and this included the construction of drifts across the Mtilikwe and Tokwe Rivers. Mac himself laid out the route, leaving his faithful work force to clear the track while he was busy in Natal. He acquired a further old second-hand truck to add to his ancient Foden, for he would have to cart all the mill components by road from the railhead at Beit Bridge.

This great task of cartage of massive and assorted items of machinery in two ancient trucks took two years, and was remarkable for two reasons: firstly, certain items were dumped in the lowveld bush near the road when the onset of rains forced a halt in the exercise, and so phenomenal was the bush growth, that Mac could not find his property until the grass and bush had died down in the following dry season; learning his lesson, Mac prudently hauled other items into prominent trees with rawhide ropes when a similar situation arose the following season. Secondly, Mac's habit of calling in to break his journey and quench his thirst at that well patronised waterhole, the Lundi Hotel on the river of that name (later the Rhino Hotel), led to him meeting there a hotel employee, Miss Marjorie Cooke, in 1937. She was to have a profound influence on MacDougall's life, and in later years she recalled how the rugged and kindly Scot with a twinkle in his eye had called lo her to join his party at the bar, saying "Come into the body of the kirk, lassie".

Soon some two acres on the chosen mill site on the east bank of the Mtilikwe was littered with hundreds of pieces of machinery, carted by Mac's two drivers, his nephew Colin Sproull, and Tom Dunuza the Swazi man who had graduated from commanding an ox-wagon to controlling one of the trucks.

Mr. Ken Kean. an engineer from Natal, was engaged in August 1938 as Chief Engineer and Mill Manager, and what a fortunate choice this was, as Kean was a mechanical wizard, and very efficiently created order out of chaos at the mill site. It was in 1938 that Mac took the advice of his close friend Billy Moubray and set about the formation of a properly organised company. Triangle Sugar Estates Limited was formed with Mr. W. Moubray as Chairman, MacDougall as Managing Director, and the other two directors were the late W. Paley of Fort Victoria and the late D. M. Milne, then Manager of Meikles Limited in Fort Victoria. Paley was a forwarding and consigning agent for the legendary Zeederberg ox-wagons and steam-wagons which hauled mining and agricultural produce and supplies in the district, and Milne, always keen on development projects, extended much-needed credit to many a small-worker or farmer.

MacDougall had always been something of a one-man band, and his involvement with the number of others in the new company introduced several interesting characters.

Geordie Muir, Mac s book-keeper for many years, was an outstanding character, a little grumpy, but loyal and industrious, and always retaining a sense of humour in somewhat primitive administrative conditions.

Billy Moubray was a tremendous ally in the Triangle enterprise, and it is interesting to rccord his part in his own words:

I come into the story really merely in the background. Mac and I were very good friends ever since I first met him in the beginning of 1926. In temperament we were quite different. I am an East Coast Scot, slow and cautious. Mac was a West Coast Scot from the Highlands, with all a Highlander's virtues and vices! But being a big character, Mac had big virtues and big faults. Perhaps we acted as a 'foil' to each other, and for that reason we got on very well together. When Triangle Sugar Estates was starting in 1938 and in the years following, I had to do most of the Salisbury end of the business, and try and put over Mac's habits in the best possible light! To give you two little instances: Mac sent me a telegram "Obtain permission to import Sugar Mill from Natal". The Customs sent me a form asking for the total weight of the machinery. I wired to Mac. Mac replied in pencil on half a sheet of paper "Put 400,000 tons, what the hell does it matter". He was quite right of course! Mac came to Salisbury to ask the Treasury for £500 to buy cattle to run on Triangle whilst the Mill was building. He was given the money. On the way back to Fort Victoria he stopped in Umvuma, saw some old machinery that he thought would be useful, and spent the whole £500 on the spot. 1 got a 'phone message to proceed at once to the Treasury. Hector Lovemore, who looked after our affairs there, was positively dancing up and down. "You can't do this sort of thing, you really can't, it's outrageous, whatever am I to say to the Minister?" I had to spend a considerable time smoothing everyone down. I used to spend a month at a time down on Triangle in those years working in the Office, trying to get all the papers in order and helping Mac with the correspondence. In spite of Mac's rather un-businesslike ways, it always struck me that he had the most extraordinary memory for details. When papers got mislaid or lost, as they frequently did, Mac's memory usually got us out of the difficulty. He was, of course, loo, a remarkable organiser. He did practically the whole of the field-work himself, with, I think, one other European from time to time. In fact, the whole of the development expenses of buying the Mill, erecting it, putting in all the irrigation works and planting the cane,, was done at an absolute minimum of cost. Any big company, or the Government, would probably have spent three times the amount that we did. When the Government took over from us they at once about trebled the staff, with, I think, no great compensating advantage."

Moubray described Ken Kean as "the key-man in the building of the mill, and a wonderful chap." It is fascinating to read Kean's own personal reminiscences of those dawn-to-dark construction days:

"Triangle was very wild in those dayst any amount of game etc. We lived in reed huts down at the mill site. There were only two of us on construction for the first few months as the company had run out of money. When I arrived there I had to sit on a lorry from Beit Bridge as Mac was laid up with a poisoned foot, having been bitten by a scorpion. After a very hot trip I eventually arrived at "Mac's" house and we chatted well into the night. Mac was very worried as no one would believe that sugar could be made in Rhodesia.

I squeezed some juice out of a few sticks of cane and boiled it outside over an open fire and concentrated it into sugar by stirring it with a piece of wood. I then got his cream separator, drilled holes in a syrup tin and lined it with butter muslin. Then separated the crystals from the molasses. I filled two Herald tobacco tins with very fine sugar, which Mac took to Salisbury. He was very friendly with Mr. Frank Harris who way Minister of Agriculture at the time. They had a meeting with certain Government people and from that Mac got his first loan from the Government.

When I first arrived there Mac had a trading store near the homestead. Old Mr. George Muir was Mac's bookkeeper, quite an old character. He later built a store near the mill, broke down the old store and built a house for me nearby as 1 had a wife and three young children. My two girls went to school in Fort Vic, and the son was home with us. Those were hard days, lots of sickness amongst the natives.

A Mr. Jock Ferric from Zaka took Mac's store over at the Mill which later was shifted near the new bridge across the river." (This of course refers to the old low-level bridge built in 1942.)

The brickwork of the boilers was done by a lovable character called Ted Gourlay, a proud stone mason of the old school, and Kean recalls that during construction a young European who had been engaged to help him, and who was apparently more interested in conversation than hard work, approached Gourlay as he laid furnace bricks and said "You know what, Teddy, I am engaged to be married." Ted looked him up and down and said "Young man, you should remain a bachelor, like your father before you."

A feature of the mill was a fine square-section masonry chimney, built by two brothers named Blignaut. Kean's assistant was a steam lorry driver turned fitter named Jock Crane, and the electrician was an Italian Joe Coupia (or Capouya?).

Ken Kean wanted a photograph of Mac atop his mill, and went to no end of trouble to rig up a bosun's chair with the aid of some huge gum poles which were ncccssary to erect the pans and evaporators, and for which Tom Dunuza had been sent to Glenlivet with a wagon. It was

a remarkable feat bringing the 80-foot poles down to Triangle over the rough Zaka-Triangle road through the hills, but Dunuza managed, and Kean duly managed to hoist MacDougall into the air and secure his photograph.

THE MILL OPENING

At last the great day arrived, and the mill was completed and running and ready for its ceremonial opening on September 11th 1939, and what a gala occasion it was. The opening ceremony was performed by Miss Marjorie MacDougall, Mac's sister, whom everybody loved and who came out from London each southern winter to spend a few months with her frontiersman brother. She later died in the London blitz, and Mac lost one of his staunchest allies.

Invitations to the ceremony were printed, and various dignitaries were invited. The Prime Minister, Godfrey Huggins, had hoped to attend, but stayed in Salisbury, as the colony had been at war since September 3rd and he needed to stay in the capital. Captain Frank Harris, Minister of Agriculture, was to have been guest of honour and to have delivered the main address, but he too was required to stay in Salisbury, and his speech was delivered by Mr. van Broembsen, the Civil Commissioner in Fort Victoria. The guests camped out next to the road just south of the mill, and early on the morning of the opening dav Ken Kean and young Capouya had a front wheel puncture while driving their half-ton truck from the homestead to the mill, veering off the road and into a tree. They both went through the windscreen, and eventually arrived at the visitors' camp streaming with blood, but fortunately not seriously injured.

Kean bound the starting wheel of the mill engine with white asbestos cord, Miss MacDougall tied a sprig of Scottish heather and an elephant hair on the big flywheel, and Mac had a Scottish standard (still preserved to this day) fluttering over the mill. After the speeches the expectant guests watched as Miss MacDougall cut a silk ribbon and opened the steam valve to start the mill, but for a moment nothing happened. MacDougall who was standing nearby leapt on the platform, kicked off a hapless piccanin who had thrown a lever in the wrong direction, corrected the lever's position with another well-aimed kick, and with a puff of steam and a rousing cheer the first crushing season in the lowveld's sugar history was under way.

There was only 45 acres of cane at the start, and only one crusher and two mills. The insatiable appetite of the boilers was fed by firewood chopped by a special gang, and 96 tons of raw sugar was produced in that first season. Mac was ecstatic, and even his severest critics and other skeptics grudgingly admitted that perhaps his enduring faith and dogged determination has been justified.

Murray MacDougall personally drove the first lorry load of sugar all the way to the refinery in Bulawayo, and it was joyfully received by Mr. Stanley Cooke, known to all as "Sugar" Cooke, who was manager of the refinery and who had always believed that MacDougall would deliver the goods in the end.

TROUBLES AHEAD

But Mac's hour of triumph was darkened even in those days by financial storm clouds on the horizon, and in 1940 Mac and Billy Moubray went to Natal where John Murray took them to see Mr. G. Crookes of Crookes Brothers, one of the largest sugar companies in Natal. George Crookes and one of his companies, showing remarkable confidence, came to the rescue and took up the balance of the unissued shares in Triangle Sugar Estates Limited.

Later, Stanley Cooke proposed that Triangle amalgamate with the refinery, and after much negotiation it was decided to launch a new company, the prospectus of which was issued in May 1941. But the company was never floated, and the Southern Rhodesian Government stepped in with additional finance, insisting on partial control, a situation which did not ever really work.

Eventually a crisis point was reached, and in May 1944 the country's young sugar industry was the subject of a lengthy debate in Parliament. Hansard reveals that the sixth session of the Fifth Parliament debated hotly a motion proposing the nationalisation of the sugar industry, and this was introduced by the Minister of Commerce and Industry and seconded by the Minister of Finance. The original motion called for the Government to take over jointly the Sugar Refinery in

Bulawayo and the Estate at Triangle.

The refinery, started by the Hornung family from Sena in Mocambique, appears to have been highly unpopular in Parliament, and the proposal for the joint acquisition was soon dropped. There was far more sympathy for MacDougall's venture; Mac had raised Government loans totally £103 000 and had spent £80 000 of this amount by May 1944. In a lively debate the Minister of Agriculture, Captain Harris, with a sense of history in the making summed up the situation when he said "The whole question today before us is whether we shall develop that very rich part of the colony or leave it for another generation to do."

With that, the amendment was carried "That the house approves the action of the Government in obtaining an option to purchase all the shares in the Triangle Sugar Estates, Limited, at a price of thirty shillings a share, that is to say, for sixty thousand pounds, with a view to the development of a sugar industry and for the development of agriculture generally, and recommends that the Government exercise the said option forthwith." It was an unusual non-party free vote of the house, and was carried by 15 votes to 9.

The outcome was that MacDougall sold out to the Southern Rhodesian Government who formed the Sugar Industry Board to take over the concern. The basis of the agreement was that the Government gained ownership of the Estate and all its assets in return for a cash payment of £60 000 and the liquidation of MacDougall's debts. C. L. Robertson, Mac's great ally, was Chairman of the Board, and Mac remained a while in an uneasy position as Manager. However, the supreme individualist MacDougall was unable to fall in with the management style demanded by an orderly civil service, and being a man of action more than words, he was soon in hot water. On one occasion he bought a small bulldozer without first consulting his colleagues, and clearly this situation could not last. So it was that early in 1945 MacDougall took leave of his beloved Triangle and Africa, and returned to his Highland home, at that stage still in the grip of the most terrible war in history. Mac was then 63 years old, and too old for active service, but he was determined to do his bit for the old country, and managed to get employment on a fishing fleet at Stornaway in the Hebrides, where he spent two years in this vital food industry.

In 1947 the cver-resourceful man got himself a lift back to Salisbury on a freight flight which took thirteen days from London, and he soon returned to the Victoria district. Shortly thereafter he arranged the finance to purchase the farm Glendale 16 kilometres south of Fort Victoria, and he pulled down and rebuilt the old house on the hill overlooking the main Fort Victoria-Beit Bridge road and facing the massive hill Cotopaxie, perhaps better known to the local Africans as

Nyanda.

MAC AND MARJORIE

Whenever he visited Salisbury he called in at the Land Bank where Marjorie Cooke was working, and the old mutual fascination first sparked at the Lundi Hotel was rekindled. They decided to get married, wondering why they had not done so years before, and the simple civil ceremony in Salisbury on December 28th 1949 was attended only by Bill and May Moubray and a young man named Bulman. Mac introduced his bride to his friends at the New Year's Eve Ball in Fort

Victoria a few days later, and those who thought they knew the rugged old bachelor better were convinced that it was a practical joke.

Murray and Marjorie were blissfully happy together, and forged a great and enduring companionship. Life at Glendale was full of interest, and the MacDougalls soon gathered a large circle of friends in and around Fort Victoria. For the next few years they camped each winter on the banks of the Lundi under a huge baobab near Bendezi hill, where Hippo Valley citrus estate now stands. They used to take their horses with them, and had many adventures riding through the bush after buffalo and other game, and they both loved fishing for the bream which seem to have been larger and more numerous in those days.

Their old friend Brigadier "Scrubbs" Hartshorn often joined them, and this remarkable man, who had lost his right forearm below the elbow in the Great War and subsequently learnt to paint with his left, produced many delightful paintings and sketchings of their camping trip, some of which are today displayed in the Murray MacDougall Museum. Mac never forgot his old retainers in the lowveld, and was greeted as a legendary figure on his visits, making many an old Shangaan heart glad with a gift of venison or mealie-meal.

In 1955 the MacDougall's toured England and Scotland in a Dormobile motorised caravan which they had ordered, and in 1957 they sold the farm and set off for Australia, where they spent more than a year, also visiting New Zealand and Tasmania. Mac even spent some time logging in a timber camp for the experience — no mean feat for a man of 71.

Returning to Fort Victoria early in 1959, MacDougall took up a long-standing offer from his late friend Alfred Gifford, settling on 100 acres overlooking the great new Lake Kyle, where Mac and Gifford had sat thirty years previously and dreamed of a great dam to irrigate the lowveld. Son Jim Gifford honoured his father's promise, and the MacDougall's soon had a comfortable and attractive home on the hillside, which they named Dunollie after the ancestral home in Scotland. They loved Kvle, and spent many happy days and nights on their houseboat "The Gannet".

PUBLIC RECOGNITION AND THE TWILIGHT YEARS

Mac was never one to seek the limelight, and wanted no part of a thought originating in Fort Victoria to have the lake formed by the Kyle Dam named Lake MacDougall. In another move which was far stronger, the I.C.A.s of the country united at their annual congress and unanimously urged the Natural Resources Board to name the great new dam the Robertson Dam, but this too was rejected, and "Kyle Dam" it remained, called after Kyle Farm, thus named by one of the Francis brothers who owned this land on the South bank of the Shagashe River. Invited to attend as a V.I.P. the opening ceremony, performed by the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, Sir Edgar Whitehead, MacDougall offered an excuse about going to Nyasaland, but allegedly went fishing mumbling that he did not want that lot talking about him!"

In the New Year Honours list of 1962 Thomas Murray MacDougall was awarded the O.B.E. by Queen Elizabeth for services to his country, and when the day of the investiture arrived Marjorie put a tie on him and took him to Government House where he was decorated by the Governor, Sir Humphrey Gibbs. Mac hated wearing ties, but was over-ruled by his wife on this occasion. However, his pride was satisfied as he insisted on wearing to Government House his old sheath knife, without which he would not go anywhere.

As the Government had refused to name after MacDougall or C. L. Robertson the lake formed by the dam built to irrigate Triangle, scene of their pioneering triumphs, the citizens of Fort Victoria, led by an enterprising young man named Tony Carver, collected funds and bulldozed both officialdom and granite to create the scenic Murray MacDougall Drive around the perimeter of the lake. In later years the Government, curiously contrite, named as Lake MacDougall the beautiful expanse of water formed by the construction of the Manjerenje Dam on the Chiredzi River to irrigate the Mkwasine estates. Mac's friends were glad of this official tribute, but as he had had no association with any part of this scheme, it seemed somehow less appropriate than the idea previously canvassed by his admirers in Fort Victoria.

Most knowledgeable lowveld residents recognised in full measure the visionary feats of MacDougall, and he and Marjorie paid several visits to their friends on Triangle, among whom were the first planters, the Starlings, Hingestons and Eastwoods. The reminiscences at these meetings of persons who had shared in the great glory of Triangle's development must have been utterly fascinating to those who love a successful human story.

The author first met MacDougall in 1962 when a Government Medical Officer in Fort Victoria. Dr. H. M. Strover, a great friend of Mac's and my "boss" at that time, was away on leave, and Marjorie phoned to say how worried she was about her husband's illness. The old man, ill but defiant, apologised for his wife's carelessness in troubling a stranger, and submitted unwillingly to examination. A diagnosis of severe lobar pneumonia necessitated treatment in hospital, and this news was not popular to the independent soul who had never really had much use for doctors. I drove my station wagon on to the back verandah, borrowed a mattress from a spare room, and carried the protesting pioneer of Triangle out to my car with the very necessary assistance of the household cook, my younger brother, and young Paddy Strover, both of whom had come along for the ride.

Mac was terribly ill and weak at first, but after a few days he started to rally. In the course of examining him I found on his back a small scar, as yet unknown to his wife. He confessed with a diffident smile that it had been inflicted with a knife wielded by a drunken sailor whom MacDougall had prevented from molesting a young lady in a South American port some sixty odd years previously.

As Mac progressed in his illness he told me about the Triangle days, and he helped to weave a web of fascination for me. I kick myself still for not recording more details about a mysterious system of ruins somewhere near the lower Lundi, which he had never got around to exploring after initially stumbling unexpectedly on them, and which he always suspected to be a fabled lost city of the lowveld. There was probably nothing in the tale, but MacDougall's magical reminiscences were in part responsible for a young medical officer leaving a Government post in Fort Victoria and seeking employment with Triangle Limited.

The management of Huletts, who had by now gained control of the Estate, acknowledged and lauded Mac's pioneering role on Triangle, and on April 2nd 1964 the MacDougalls were picked up in Fort Victoria by the company's private aircraft, and flown over the whole area. One can imagine the wonder and pride which stirred his heart as he and Marjorie gazed down at the sparkling waters of Kyle, Bangala and Esquelingwe, and the great Kyle Canal snaking its way for 60 km through the massive green hectares of cane on Triangle and Hippo Valley to the dark green orderly citrus estates on the Lundi, while smoke billowed into the sky from two giant sugar mills. Murray MacDougall's dream of a great sugar industry was a dream no more, and there were tears in the old man's eyes as he watched the chained bundles of cane being unloaded at Triangle Mill.

The branch railway line from Mbizi was on its way to Triangle and Chiredzi, and soon the sugar from the two factories would be transported by rail to the refineries elsewhere. Mac confided to some of us that he would die a happy man if he could stand on the footplate of the locomotive hauling the first load of sugar out by rail from Triangle to Mbizi. He was to be guest of honour at the official opening of the new Triangle Mill by the Prime Minister in June 1964, an event he looked forward to with eager anticipation, and he had received a special note from C. A. Gibbs, Business Manager of Triangle Limited, informing him that he need not wear a tie to the ceremonial opening.

But it was not to be, and the indomitable spirit was finally stilled on 30th May 1964 when Thomas Murray MacDougall died from a stroke in St. Anne's Hospital. Salisbury. Down in the lowveld Mac's old hunting ground along the Cliredzi River was the scene of a touching moment, as Ray Sparrow, having received a telephone call, went sadly to Kwali Glen on his Lone Star Ranch where Scrubbs Hartshorn had come to spend the winter as he had done for so many years. "Mac's dead" was all he was able to mumble in response to the greeting of the white-bearded old warrior. Hartshorn, eyes moist, slumped into a deck chair and stared a long while into the river, his grief shared by his old cook MBangwene, who had shared many camps with the two of them under the bright stars of the lowveld winter nights.

A memorial service oil the village green at Triangle was attended by many of his friends and admirers, and hundreds of Africans from all over the lowveld gathered to pay homage to the legendary "Meke", for lhey remembered him as a man of strength and justice, an accomplished Shangaan linguist, who had travelled among them many times on his horse, carrying only his gun, a bag of tobacco and a bag of salt on his belt, sharing their evening fires and their mealie-meal porridge, shooting game for their meat, and helping them out with food in times of drought and hardship.

Later in a simple ceremony, performed by his old friend and companion. Brigadier Scrubbs Hartshorn, Mac's ashes were laid to rest in a large rock under the marula tree in front of his house on the hill.

A few days later, at the gala opening of the mill at which MacDougall was to have been the guest of honour, at the express request of Ross Armstrong, Chairman of the Board, Mac's seat of honour next to the Prime Minister was left vacant when Ian Douglas Smith performed the opening ceremony, a poignant and moving tribute to the passing of a remarkable person.

Truly, this was a man among men, and his example of courage and determination remain as an inspiration to many of us. his memory perpetuated by the Murray MacDougall Museum, the Murray MacDougall Scholarships and the Murray MacDougall School. I have a feeling that the rugged spirit of Mac keeps watch over his beloved Triangle from the top of the hill to this day.

End of Part 1

Click Here to Return to Index

PART I

THE STORY OF MAC

This is the life story of a legendary Scot, a man of vision and courage, who, at the beginning of this century, came from far off places to the wild lowveld, saw its great potential, and determined to tame it. Many men followed his inspiration and prospered.

This is the true story of Murray MacDougall, founder of Triangle and lone pioneer of the Lowveld's irrigation schemes.

This is the true story of Murray MacDougall, founder of Triangle and lone pioneer of the Lowveld's irrigation schemes.

Thomas Murray MacDougall was born on 4th March 1881, on the farm Auchnashelloch on Loch Awe, Argyllshire, Scotland, close to the family seat at Dunnollie Castle, about which Sir Walter Scott wrote "Nothing can be more wildly beautiful than the situation of Dunnolly, the ruins are situated on a bold and precipitous promontory, about a mile from the port of Oban." The MacDougalls were a proud and independent Highland family, known for their initiative and love of adventure, and so it is not surprising that many sons of the clan had seen distinguished military service down the centuries.

It was traditional amongst the Highlanders or those parts that on the birth of a son the head cowman should carve from a cow's horn a porridge spoon, and the infant MacDougall was duly presented with a fine spoon which is preserved in the museum to this day.

Murray MacDougall had a good start, with coarse-ground oatmeal porridge to begin each day, and plenty of fresh air and exercise on the farm, for his father believed firmly that youngsters should have a strict and vigorous upbringing. As a Highland lad growing up on his father's farm, Murray showed at an early age that he had inherited in full measure his ancestors' qualities of rugged resourcefulness and zest for life,

His father was a farmer who also owned interests in a banking concern in Glasgow, and during a severe recession of that time the family suffered crippling financial setbacks, and so it was that at the age of fourteen it was found necessary that the young lad should leave school and seek work in an attempt to assist the family. He found employment as a general hand in the shipbuilding yard of the giant firm Cammell, Laird & Co., where he soon gained the admiration and respect of his much older workmates.

It was here that MacDougall gained a love of things mechanical, as well as the practical expertise which was to stand him in such good stead in the years ahead, and as an interesting sidelight he gained something of a reputation for his ability to cook steak on a shovel for his workmates.

MacDougall was known as Murray to his family and his closest friends, and as "Mac" to everybody else, and he was never called "Tom" by anybody except in his late life. This appellation, to his great annoyance in his last years, was incorrectly credited to him by an ignorant or presumptuous Rhodesian press, presumably on the assumption that anybody with the first name Thomas should be called thus. (The management of Triangle Limited blundered similarly in the early 1960's by calling the company's first locomotive Tom MacDougall', and by so labelling a framed photograph hanging in the company's main office block. It is a fair bet that anybody reminiscing, either wistfully or proudly, about his close association with "Tom" MacDougall in the good old days, is guilty of name-dropping and did not really know him well.)

At the shipyards Mac met many interesting characters, and listened spellbound to their stories of distant places, and his urge to travel and thirst for adventure led him to sign on as a hand on a cattle-boat which was sailing for the Argentine. He left with the blessing of his family, and throughout his life maintained the strong family ties of his clan, despite his fiercely independent spirit and prolonged absence from the Highlands of home. He treasured through all his wanderings his tangible links with his clan and family, among which were a locket given him by his mother and father, containing their miniature portraits, and an inscribed bible from his mother, and all his life he had a MacDougall tartan rug on the end of his bed.

Having arrived in South America, he made his way through several countries, seeing something of Brazil, serving in President Castro's army in Venezuela in 1898, and eventually landing up in British Guiana (now Guyana), where he obtained employment in the sugar-cane fields of Demerara, for a salary of six pounds a year and his keep! A mistaken idea has somehow arisen that MacDougall obtained his inspiration to grow sugar-cane at Triangle in later years' because he recognised instantly the similarity between conditions there and those of Demerara. Nothing could be further from the truth, as the Guiana fields were in swamps, requiring ingenious drainage systems to avoid flooding, and providing an interesting opportunity to transport cane to the mill on rafts.

Mac acquired a life-long aversion to pork while at Demerara, as there was apparently a large population of feral pigs gone wild and living in the cane. These were called to be fed on molasses by blowing on a cowhorn and they were regularly harvested and used as a staple ration for the men. One skill of great subsequent benefit which Mac picked up at Demerara was that he learned the principles of surveying, a factor essential in Demeraras canal and drainage system, and later to be a priceless advantage in his early days at Triangle when laying out his irrigation system.

The hard work and rigorous outdoor conditions in South America ensured that MacDougall matured physically, and by his twenty-first birthday he had filled out and was a tall and strong man.

AFRICA CALLS

Early in 1902 Mac again succumbed to the urge to move on, and he eventually obtained a working passage in a ship bound for South Africa from the United States, whence he had travelled after leaving Guiana.

On arrival in Cape Town Mac enlisted in the South African Constabulary to serve the Crown in the Boer War, but before he saw active service the war ended, and Mac was discharged from the force and set about finding a job. He travelled to Natal and joined a cartage firm. He soon demonstrated a natural flair for handling transport animals, and in a very short while he obtained a wagon and a team of mules of his own, and became an independent transport rider. His services were much in demand, and he carted supplies through Northern Natal and Swaziland, eventually making his way to the Eastern Transvaal, where there was great activity on the goldfields in the Barberton/Lydenburg/Pilgrim's Rest area.

The bracing climate, bare hillsides, and rushing mountain streams must have reminded Mac of his Highland home, and this impression was probably reinforced by the presence of many of his countrymen in the district. Indeed there had for so long been so many Scots working in the area that President Burgers of the Transvaal Republic, on a visit to the region in 1872 named one particular camp MacMac, a name which has persisted to this day. MacDougall spent three happy and vigorous years in this historic district, further enhancing his reputation as a skilled transport rider and a man of good character and high principles.

During the summer rains it was not possible to do much work in the haulage business, and Mac took to travelling around and seeing the country at these slack times. So it was that in 1906 he travelled north on horseback, leading a pack animal with his kit. He crossed the Limpopo and pushed on northwards through the lowveld bush until he reached the Mtilikwe River, in which vicinity he spent an enjoyable few weeks hunting, and making the acquaintance of the handful of Shangaans who lived along the lowveld rivers of this wild, unexplored, and virtually uninhabited corner of Southern Rhodesia.

MacDougall fell in love with the area, probably among the first white men to fall victim to the strange fascination of the lowveld, and he vowed to return one day.

Trekking back to the Transvaal, he secured a contract at Pilgrim's Rest carting supplies for the hydro-electric scheme being constructed on the Blyde River, below the Bourke's Luck pot-holes, to supply power for the goldfields. For two years he worked on the scheme, saving his money and investing in better wagons and pack animals, taking time off to serve as a volunteer in (he Zulu Rebellion over the border in Natal in 1907. and being awarded the campaign medal.

At the end of 1908 he decided to make the move to Mashonaland, and he led a party northwards through the wild country he had traversed two years previously. In his party were six white men, a coloured man, and nine blacks, including a young Swazi piccanin, Tom

Dunuza, who had joined Mac at Carolina in the Transvaal on a previous trip, and who was later destined to become one of the great characters of Triangle.

Crossing the Limpopo, the party trekked straight on to Salisbury, where Mac lived for the next four years, delivering stores and supplies, mining equipment and building materials to the gold mines in the Mazoe Valley and surrounding districts. He became famous throughout Mashonaland for his skill with his mule teams, and once drove a fully laden wagon up the very steep hill to the Bernheim Mine at Mazoe, which was regarded as an extraordinary feat in those days.

In 1912 famine following prolonged drought threatened the south-eastern area of the country, and the Government appealed for help in carting grain to the starving African people of the Victoria district. Mac travelled with his grain down to the Bikita and Zaka area, and took the opportunity to revisit on horseback the uninhabited area on the lower Mtilikwe. He experienced again the irresistible fascination with which the lowveld had earlier gripped him, and decided to do something about it.

On return to Salisbury he applied to the administration for rights to 300000 acres of land between the Mtilikwe, Chiredzi and Lundi Rivers, but, as there were no maps of the region and no surveys had been performed, there was an understandable delay in formalising his grant, but he was given an option on the land. Mac moved to Triangle, followed naturally by the sturdy young Tom Dunuza, but before he could contemplate any development, the Great War broke out in 1914.

MAC THE WARRIOR

Along with so many of the cream of the Empire's youth, MacDougall answered the call to arms, travelling from Triangle to London, and enlisting in the First King Edward's Horse. He went abroad with the British Expeditionary Force, and served with distinction in the First Battalion, the 18th London Regiment, attaining the rank of Captain. His great experience with the mules so vital to the war efTort in the First World War led to his appointment as Brigade Transport Officer. He was twice mentioned in dispatches, and was awarded the Military Cross. His army pay-book, preserved in the museum, records the award as follows:

"CITATION ON OCCASION OF AWARD OF MILITARY CROSS TO

LT. T. M. MACDOUGALL.

Lt. Thomas Murray MacDougall, London Regiment, for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty when bringing up a train of pack mules with supplies to his battalion. With exceptional skill and fine judgement he sent his convoy singly through heavy barrage, afterwards re-assembling them and delivering his supplies without casualties. This occurred in complete darkness, and his example of personal courage and decision was invaluable to his men.

Battle of Messines

June 7th 1917."

MacDougall took great pride in his work, and his iniative and practical bent of mind led to his invention of an ingenious mule saddle designed specially for carrying ammunition for the field guns.

On his discharge from the army after the armistice, Mac's Commanding Officer sent him the following commendation:

"Lt. T. Murray MacDougall acted as brigade transport officer for almost a year — his thorough knowledge of animals and transport work was of great value at all times. He understood the management of men and how to get things done. He has always behaved with gallantry, notably in the Ypres Salient — the operation including the battle of Cambrai in November and December 1917, and during the withdrawal after the great German attack on March 21st 1918, when he succeeded in bringing all the animals and transport of the Brigade intact through an extraordinarily difficult and trying period — an extremely capable and efficient officer.

William J. Mildren

Brigadier General

Commanding

141st Infantry Brigade"

As soon as MacDougall was brought back to London with his unit at the end of the war, he hurried back to Salisbury intending to lose no time in returning to his beloved lowveld to start development of his ranch, but he was furious on finding that while he had been on active service his land had been promised to somebody else. Unable to make any headway in his protestations in Salisbury, he returned to London determined to assert his rights in the highest places. In later years he recalled with a broad grin how he demanded, and was granted, an audience with the Directors of the British South Africa Company, during which he thumped the boardroom table and expounded his claims in uncompromising language.

To their eternal credit these influential gentlemen upheld his appeal, and, clutching a precious document authorising his grant to his promised land, Mac boarded a steamship bound for Cape Town.

When MacDougall commenced his return to Cape Town the great 1919 influenza epidemic was raging, and many of the crew were smitten by the disease during the voyage. MacDougall's strong constitution enabled him to escape the illness, and he fell to willingly to lend a hand wherever needed. Thus it was that his tremendous initiative and versatility were fully utilised by the captain of the ship, and Mac found himself acting at various times as purser, steward, assistant mechanical engineer, and navigation assistant.

On arrival in Cape Town it was round that the flu had the city firmly in its grip, and many poor people, in particular, were dying from the disease. An appalling situation had arisen due to a high mortality in District Six, as most people were afraid to enter the slums lest they too should succumb. Shrugging off the danger, MacDougall undertook to transport bodies of deceased persons from District Six to the cemeteries, the only payment he requested being a case of Scotch whisky.

He eventually arrived back in Salisbury, re-established his rights to his land, and was granted an option on 300 000 acres of land, now roughly comprising the properties of Triangle, Buffalo Range and Hippo Valley Estates, for an ultimate purchase price of fourpence an acre.

EARLY DAYS ON TRIANGLE

Murray MacDougall had always wanted to ranch cattle, and in Fort Victoria he met another well-known character, Mark Spraggen, with whom he struck up a partnership. They named the property Triangle after the registered cattle brand which Mac purchased from a fellow farmer named Van Niekerk, as the poor chap was going out of business and had a very simple brand which almost defied alteration in a period when rustling and brand-changing was not uncommon. For a few pounds Mac purchased both the registered brand itself, in the shape of a simple triangle, and the branding irons to go with it.

Mac rode down to the ranch with his cattle and his wagons, forded the Mtilikwe, and pitched camp under a large baobab tree across the Cheche stream, not far from the present new supermarket. It was said by his old hunting partner Scrubbs Hartshorn that Mac spent his first night on Triangle Ranch under the old marula tree on Mac's Hill beneath which his ashes now lie in a simple stone monument.

A clean water supply was one of the first necessities, and with a handful of Shangaans armed with picks and shovels, and a few sticks of dynamite, he sunk a well near the Cheche, close to the present mill site, making a rough windlass from mopani poles, by means of which the earth and stones, and eventually the water, were hauled to the surface in a bucket on a rawhide rope. Then came the construction of the cattle dip, on the eastern bank of the Mtilikwe River close to the present C.A. Gibbs Bridge.